ARTS MARKETING IS COMING FOR YOU AND YOUR KIDSOne of the most frustrating and perverted words in contemporary American language is the word “creative.”

No, I don’t mean the creativity of God — we’ll get to that — nor even the “subcreations” of boys and girls of all ages, which come in the form of the Arts — we’ll get to that also.

What I’m referring to relates to a common job title in the marketing and advertising industries called “Creative Director.” These folks usually oversee vast-scale projects with many underlings and trusting clients — the “creative director,” for expediency’s sake more than anything, has to make a myriad of “creative” decisions, from copy-writing to what color is used on a billboard. In other words, the Creative Director is needed to thwart the endlessly debatable decisions a deadline cannot tolerate. In a complete democracy, nothing is ever accomplished. There must be a someone who functions as a visionary.

“Creative Director,” as a title, has a double meaning. It is firstly an inflated job title, a more flattering and “artistic” description of what can also be called a “project manager.” But more importantly, the word “creative” in this context also refers to two uses of the word “creative” that, according to an article from Merriam-Webster, have skyrocketed in popularity over the past 10-20 years. Both uses are as nouns. The first describes, or rather self-describes a person — a person whose personal vocation and present or aspiring career path is to “be a creative.” A plural noun follows, “A group of creatives walk into a bar.” Such a sentence is fundamentally different from “A group of artists walk into a bar,” since the occupation of the “creative” is to create something only in the universe of what’s marketable, whereas the artist simply creates. If you want to hear the word “creative” used in this way, watch content online related to arts marketing. Musicians, for instance, mostly left on their own to run their careers with the rise of social media, are desperate to market themselves online, so there is a lot of DIY marketing content for them to consume, which is very popular and therefore pushed by the algorithm. Essentially, musicians (and other types of artists) have unconsciously and wholeheartedly adopted language that was once exclusive to the advertising industry into their own works and lives.

The second noun use of “creative” refers to the piece of media you use in an ad for Meta products such as Facebook and Instagram — and last time I checked, Twitter as well. So if your Instagram ad is a video, that video is called your “ad creative.”

So, one can think of the “Creative Director” as a “director of creatives,” referring to people — and also a “director of creatives,” referring to advertising assets. Semantics, semantics. Language is fluid and messy, duh. Verbs become nouns all the time. Why does this matter?

I just find it alarming that artists, who may or may not be talented or create beautiful works, are unwittingly adopting language from the advertising industry not only to apply to their works, but to themselves. Record labels are currently only scooping up musicians who have already had some online success, and so musicians are on their own, using a combination of their own marketing cleverness and the whims of the algorithms to shoot them into the orbits of success. There are no A&R executives searching the open mic nights for fresh talent to exploit yet also taking up the burdens of marketing in exchange for such exploitation. The result is that artists feel they have to market themselves on their own. They have to become the human equivalent of a Facebook ad. The fusion between a “creative” (that is, an artist marketing themselves online) and an ad “creative” asset has become one, creator and created fused into a single, contrived online personae.

I credit this is as a primary reason why musical culture has been stagnant for almost a decade. Not only is mixing arts and marketing extremely dangerous to the mind and soul — I’ve seen TikToks of aspiring pop stars crying on camera because of their exhaustion trying to market themselves online — but it just simply doesn’t work. Something’s gotta give, and it’s either going to be the marketing or the art.

So, I see no option but to reset the notion of “creativity” altogether. We cannot allow elite forces to manipulate young artists into believing they need to market themselves to death in order to justify their motivation to create artworks, or that they must conform to popular styles. This has always been a tendency, but there has always been a counter-establishment avant-garde to keep the marketable arts in check. But the democratization of the internet Algorithm has made the Establishment more vague, turning what was once an elite gatekeeper into an anonymous amoral robot. The nature of culture has become vague at best and an overwhelming mess of confusion at worst. Therefore, no counter-culture can exist because there is no clear culture. The mythos of the “undiscovered artist” who is against and outside the world has lost its magic. There is no romance to one’s art being placed on the same internet platforms as Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, but without their lustrous numbers. Spotify is a marketing platform, not a record player. No wonder musicians chase the numbers.

Hopefully, if I can reestablish the ideal form of the artistic impulse, why it exists within us, what it’s for, then we can create Art as a necessary and religious aspect of mankind, and the notion of “creativity” can disappear altogether in its fusion into the complete and unadulterated human being.

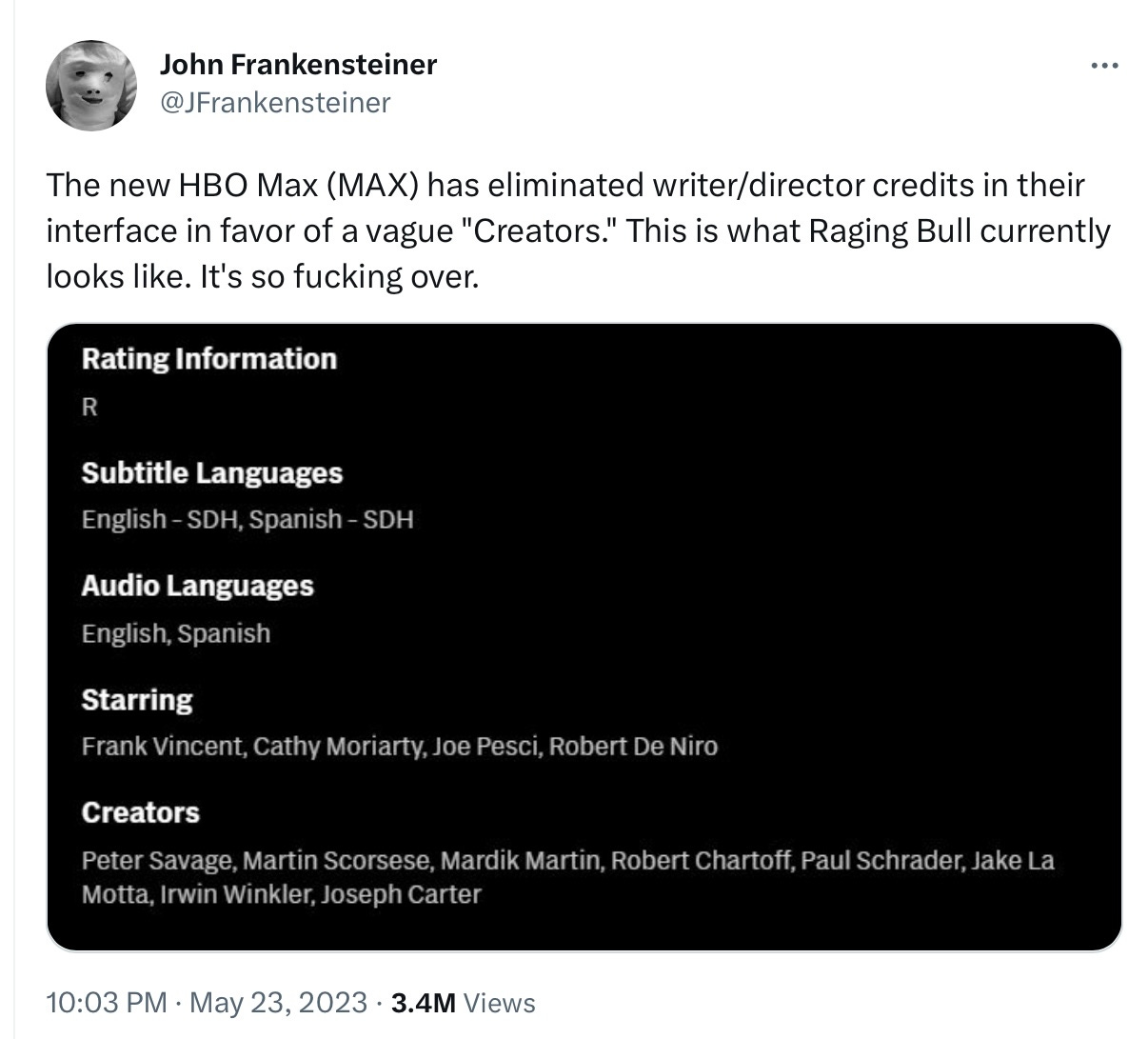

INTERLUDE: STREAMING PLATFORM TURNS FILMMAKING INTO CREATIVITYWednesday, May 24, 2023. The headline of the day: “HBO Max” is now just “Max.” You say “that happened.” Then, you see an insidious tweet:

A new era has been brought in. There are no longer writers, or directors, or set designers. There is no longer any hierarchy of significance in the collaboration on a work of art. They are all flattened into “creators” — a euphemism of “creatives” — organized in no coherent order.

Even if Max fixed this tomorrow — and I predict they’ll refine this feature and possibly remove it entirely based on criticisms already seen online — it doesn’t change the fact that, for even a day, such a gross and offensive flattening of art into “content” made by “creators” was allowed to pass through the stages of UI development, which I can only imagine involved at least a few well-attended meetings.

ANYWAYS! LET’S RESET WHAT “CREATIVITY” IS :)Creativity is not special.

This is a myth that comes from our culture’s perception of childhood. The idea is that children are purer, more special beings than adults. And they’re also more “creative” than adults, and more “imaginative,” although it is never clearly defined in what ways this is true. Because children are special, and children are “creative,” therefore being creative as an adult makes you childlike and therefore special. But again, how are children more creative than adults? If the definition of “creativity” is that children are more active in creative endeavors, in the sense that they draw more, play games, and make up stories more than adults, then I suppose that would be true, although this creativity is instantly thwarted if you put an iPad in front of them. But if creativity is defined as creative or artistic potential, then it is certainly questionable whether children are more creative than adults. Adults don’t lack creativity because of a lack of potential, but rather because they face a variety of blockages that prevent their potential from developing, whether that be artistic indifference, self-consciousness, self-loathing, jadedness, being “too busy,” and a variety of other grown-up problems that children generally lack.

The main thing preventing adults from indulging in the arts, aside from indifference, is that they buy the myth that it requires talent. There is much to blame for the “talent myth,” but I will say one thing. Singing, one of our culture’s most revered “talents” (as shown by shows such as American Idol and X-Factor) is also perceived as something someone is born with, and thus is unable to learn. Our culture takes this for granted. However, as someone who has taken vocal lessons with several professional voice teachers and has watched dozens of different voice teachers online, all of them unequivocally agree on one thing: everyone can learn to sing, except maybe the ~4% of the population that is tone-deaf. And yes, of course, certain singers have voices that our culture finds more appealing than others. A gifted soprano is usually preferred in pop music to an equally gifted baritone. But the point is that the myth of “singing talent” is a creed of a culture that falsely perceives artistic skill in general as special, or a genius one is born with. But even great singing talents like Arethra Franklin and Amy Winehouse trained extensively in music as kids, but of course that was before we saw the fruits of their labors. Before the vinyl record elevated the pop star into the realm of the gods, everyone could sing, and did so in their churches and with their families.

Creative endeavors don’t need to be “good.”

When you listen to someone like Daniel Johnston banging away at a chord organ, or look at some of the manic paintings of the Art Brut movement, what you see are not attempts at making something “good,” but rather something that can only be described as the expression of an excess of energy. This expression of energy has a “goodness” to its expressor that is separate from, and arguably more significant, than the audience’s perception of the “goodness” of the finished product of that expression. The problem with “goodness” as it’s commonly perceived is that it separates the process from the product, because “goodness” can only be aspired to through comparison with finished products in which the process of their making are invisible to the audience. Therefore, the full picture is lost and the sufficient information required to make a comparison ends in illusion. Also, a masterwork of art or music is a finished piece of history and therefore cannot be replicated. Models of success can be an inspiration for artists, but due to their non-replicability they become a distracting stumbling block for artists. Art Brut artists are worth studying because they generally don’t have to deal with these kinds of stumbling blocks.

There’s also the theological notion that the creative endeavors of Man will never actually be “good” because they are like child’s play in comparison to the glory of the source of all Good, that is God. As Jesuit theologian Hugo Rahner writes in Man At Play,

“even the greatest deeds of men are but children’s games compared with the perfection which our souls desire or the perfection that is in God himself. Indeed, in all his thinking, his pondering, his fashioning and designing, he is but a poor imitator of the Logos, the Heavenly Wisdom who plays upon the earth, the co-fashioner with God.”1

There is also an echo in J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of “subcreation,” as extrapolated in his essay On Fairy-Stories and succinctly poeticized in his Mythopeoia:

“…man, sub-creator, the refracted light / through whom is splintered from a single White / to many hues, and endlessly combined…”

Man’s sub-creation, then, is not “creative” in the sense of additive, but actually more like a refraction from a greater whole, which is more like a subtraction. He goes on,

“…Through all the crannies of the world we filled / with elves and goblins, though we dared to build / gods and their houses out of dark and light…”

There is no speak of creating abstract “goodness” out of the æther through a purely man-made will-to-power. Our only mission and ability as sub-creators is to create Elves, and Goblins for them to fight. We can only create corporeal entities that point to the Mystery, and all the “goodness” in our works is not in what they are, but what they point to.

Creativity doesn’t need to be seen by the public.

We take for granted that our culture values art based on its fame and level of exposure rather than its existence in itself. Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, on the other hand, doesn’t take this value for granted, but instead places the value in the other direction, that too much fame can actually hinder a work of art. As he writes in the first volume of his Glory Of The Lord,

“Works of art can die as a result of being looked at by too many dull eyes, and even the radiance of holiness can, in a way, become blunted when it encounters nothing but hollow indifference.”2

The desire for art to be public is especially a problem for musicians, since music has become the most commercialized out of all the art forms. Many musical artists, on their social media, hammer the garish phrase “[ALBUM] OUT NOW” in all-caps in their bio, pointing to a link to said album to be consumed on every streaming platform you’ve heard of — and every streaming platform you haven’t heard of. There is no information about what the album is, who it’s for, and why a stranger on the Internet should listen to it. The hype of the “album drop,” as paved by the example of actual pop stars has trickled down to actually unpopular “unsigned artists.” They are faking fame until, they think, they can make fame. And then they get discouraged when no one seems to care.

Many significant artworks and art movements began as private endeavors, or for a small group of friends. Others didn’t have an audience at all, not even their own mother. Let’s list a few: Gerard Manley Hopkins, Emily Dickinson, William Blake, Henry Darger, Van Gogh, Franz Kafka, Nick Drake. Writers like Poe, Thoreau, Melville and Keats, meanwhile, had the 19th century writers’ equivalent of 20 monthly Spotify listeners. Let’s be clear: One should not aspire to be a posthumously famous artist, because there is little common denominator amongst these names in which to aspire to. They share no “formula for success.” Hopkins, for instance, seemed to write poetry not for entertainment or beauty in itself, but as an act of ascetic sexual sublimation for the homoerotic temptations he struggled with as a Jesuit priest.3 Van Gogh and Blake worked in fevers, Kafka and Drake in melancholies, and Dickinson wished to make a religion of the individualistic American whose Church was your room and the world around. Whatever the motivation of these artists were to create — and of course there’s much speculation as to their motivations, and much more romanticization — it is obvious that their common denominator was that their unanimous disgust for marketing to the wide public and compromising to appeal to them was of the same flesh and blood as the quality and uniqueness of their work which led to their inevitable remembrance.

Christ’s promise “In my Father’s house there are many mansions”4 is a whitepill for artists. Notice the language of privacy — this image of the Kingdom is not of one large room, with everybody connecting with everybody all the time. It is a paradox of Heaven — we are separated by our being in different “mansions,” but not isolated, since we are unified by the Father’s house. We are called to find our own mansion on this Earth during our lives, but since in the fallen world we are not all unified under the Father’s house, most people just aren’t going to like your mansion. And the worst thing you can do is, in the rhythm of Balthasar, let your mansion crumble by being “looked at by too many dull eyes.” In this context, he would mean that the discouragement we feel from indifference or bad criticism can lead to a kind of bitter self-reflectivity that prevents our mansion (our Great Work) from being fulfilled. And for so many, this breakdown can happen at the stage when we believe our mansion is close to presentable, when in reality, only a few planks have been laid down.

Creativity is simply the fundamental expression of learning, and therefore its fundamental purpose.

The artist of my ideal must rebel against specialization. There is both a spiritual/Hermetic/Catholic reason for this and a practical one. Let’s start with the former.

Specialization is the ideology of the dinosaur. Dinosaurs were specialized during their time — excellent in brute strength and force — and for this reason, they had dominion over the Earth… for a time. The mammals, on the other hand, were less specialized, smaller and humbler, but better able to adapt to environmental and climactic changes, and therefore, despite their relative weakness to dinosaurs, the mammals survived and the dinosaurs did not. This counter-intuitive fact is course a foundation of Christian imagination as instituted by Christ on the Sermon of the Mount, through which Valentin Tomberg expresses a great unifying truth of biology and spirit in Meditations on the Tarot:

Therefore, expressed in biological terms, “to exalt oneself” amounts to specialization, which gives temporary advantages, and “to humble oneself in order to be exalted” means, in terms of biology, general growth…” 5

We see how this dinosaur ideology plays in the world of art as seen on social media. It is considered best to do just one thing, to have one gimmick, that makes you predictable and instantly appealing to your followers on social media. There is no room for the polymath on Instagram. But of course, gimmicks are cool at first, and can get you popular quickly, but soon they grow stale — and you’ve spent so much time focused on building the tower of your gimmick that you’ve neglected your garden of adaptability.

For it is the way of general growth or that of “humbling oneself to the role of a seed,” in opposition to the ways of specialization or those of “exalting oneself by building towers,” which sets this text in relief.6

Specialization, then, according Tomberg, is anti-Christian, since it is basically an expression of pride. And I would agree. If modern man is, as Chesterton says, “the heir of all ages,” then the Catholic is to take this seriously, and not blindly sell the estate-of-all-ages like the modernist would. And thankfully, some Catholics have taken this call seriously, considering how classical/liberal arts curriculums are popular in faithfully-Catholic colleges and home-schools. And such a curriculum is essential for surviving, adapting, thriving in a world filled with fallen hearts, distorting ideologies, malevolent and confusing spirits, changing fashions, sensorial disorientation, complex social relations, disguised heresies, and modernist conceits. We are in a perpetual Cross, a perpetual dying and becoming, constantly on the brink of collapse and only helped from the cliff by the grace of God — and here we are, worrying about finding our gimmick that will make strangers online click the Like button. Or, making a “career,” — otherwise known as the final death-stamp of specialization.

Learning, especially in a non-specialized way, is the antidote to all experience. If learning is considered a virtue, one that leads us closer to God, and it is true that man can learn from any experience, good or bad, then we should place learning at the center of our lives. For artists, it should even be placed above “creativity.” Creativity should be a servant of Learning. Perhaps we make a song to learn about how to order our manic passions correctly, or paint to learn about how the human eye sees nature. Perhaps we write a solemn poem to learn how to transform our disorienting experience into order, or perhaps we put on a campy and whimsical play to learn how to transform our orienting experience into (playful) disorder. When learning becomes the goal of creative endeavor, all art is transfigured — even if it is a failure with no audience.

CONCLUSION: HOW TO BE JOHN THE BAPTISTWhen I was confirmed on Easter, I chose St. John the Baptist as my confirmation saint. For artistic purposes. And as an avant-garde artistic statement.

Here is the statement: I will not be great — I will pave the way for greatness.

This, I believe, opened up the doors of freedom for me as an artist. There are so many wildernesses to explore, beasts to tame, trees to climb. New souls are always being born! Let us machete trails through the jungles of contemporary life for them to explore without getting caught in the vines or bitten by snakes. Art opens wonder, which means it opens alternatives to the lowercase “world,” ruled by the false “prince.” May I, through whatever arts may fall upon my lap of inspiration, create just one more avenue for even just one soul to go down, such that they may be likewise inspired to create avenues for others as well — this I pray. For the public, the mainstream, the crowd — can they fit through these narrow gates created by the true artist? Can they find these trails paved for one, as John the Baptist paved a trail for one man in particular, the God-Man, Christ himself?

Writer and sophiologist Michael Martin seems to be of a similar mindset — and indeed, his work and thought has been an inspirational aid in this essay.7 John the Baptist is, for Martin, a model for artists of the contemporary world, and especially as an antidote to the marketing-poison I purport in this essay. So, I leave you with a brilliant summary of John the Baptist’s role for artists, as written by Martin in his great book Transfiguration:

Any Christian art worthy of being called “Christian” or “art” should be grounded in the future. John the Baptist, therefore, is the archetype of the Christian artist: for he calls the Messiah out of the future. The Baptist, while simultaneously embedded in a tradition, nevertheless lives in the wild, on the outskirts of that tradition, a prophet of “the wild Being.” He is of the tradition, but not in it. He does not listen to criticism. He does not solicit advice. He does not fear death. He does not network or build his resume.8

St. John the Baptist, pray for us.

Hugo Rahner, Man At Play, pg. 43

Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics, vol. 1, Seeing the Form, pg. 23.

This is argued elaborately in A Queer Chivalry by Julia Frances Saville (University of Virginia Press; Illustrated edition (May 29, 2000)

John 14:2

Meditations on the Tarot, Letter XVI, Pg. 449

Ibid.

I credit Michael Martin for introducing me to the von Balthasar quote mentioned in “Creativity doesn’t need to be seen by the public,” since he quotes it himself to advance a similar thesis as myself in his book Transfiguration. Shoutout to Michael!

Michael Martin, Transfiguration: Notes Towards A Radical Catholic Reimagination of Everything, pg. 37. Italics and bold mine.